White Sands National Park, located in the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico, is home to the largest collection of human footprints. One of the more recent findings has placed the arrival of humans settling in North America thousands of years before what was previously thought.

According to a news release from White Sands National Park the recent discovery is evidence humans inhabited the region at least 23,000 years ago. Researchers used carbon dating on grass seeds found at the same level as the fossilized human footprints to determine the age of the footprints.

“These incredible discoveries illustrate that White Sands National Park is not only a world-class destination for recreation,” Park Superintendent Marie Sauter said in the release, “but is also a wonderful scientific laboratory that has yielded groundbreaking, fundamental research.”

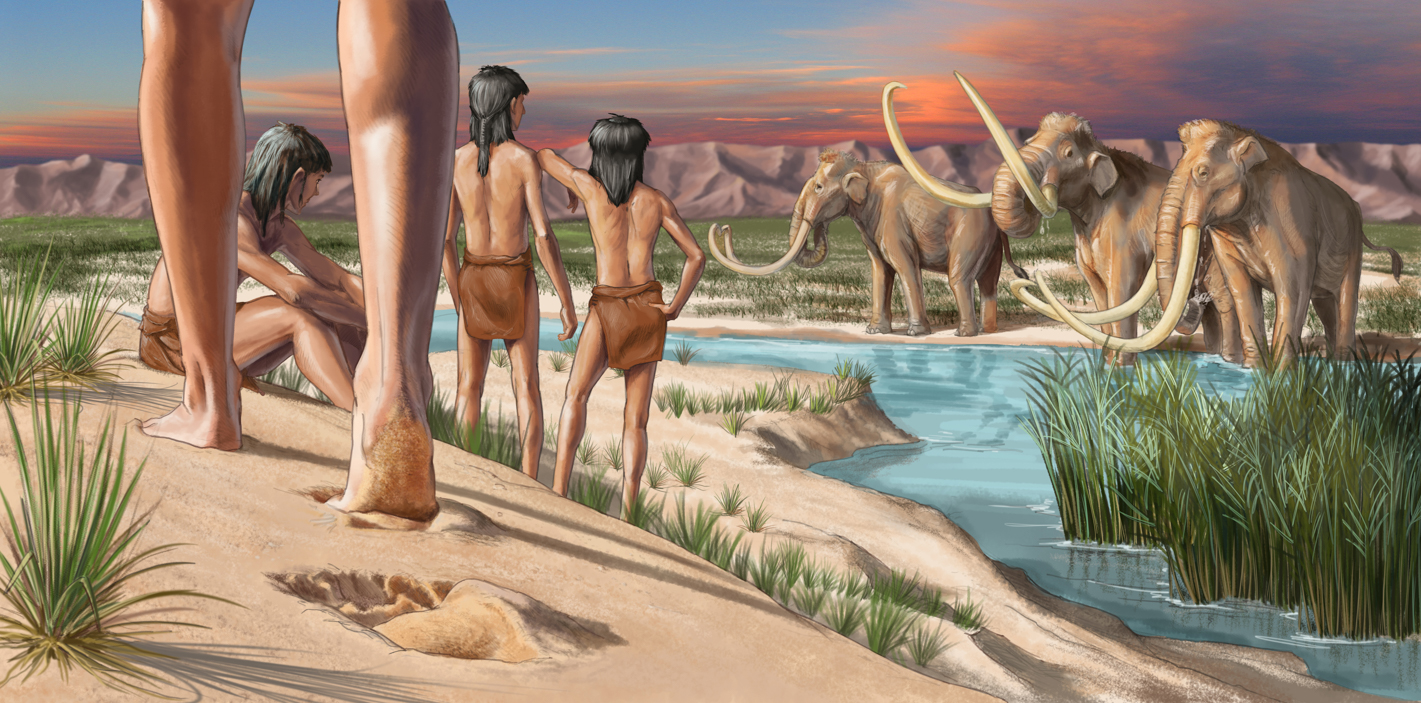

This new finding also means humans in North America lived longer with the local megafauna than previously thought. Historians have long debated what caused the extinction of the megafauna, with overhunting by humans often held as a top contender along with climate change. Many experts believe the extinction was a combination of many factors, but pinpointing which factor had the most impact has been an area of intense debate.

Now with humans and megafauna coexisting for thousands of years more than previously assumed, researchers will no doubt rethink their hypotheses.

“This study illustrates the process of science – new evidence can shift long held paradigms.”USGS Acting Rocky Mountain Regional Director Allison Shipp

White Sands National Park is known as a “megatracksite”, a location with a particularly high abundance of fossilized footprints or tracks, or other trace fossils. Human footprints aren’t the only tracks that have been found and studied at White Sands. Many ice age species show up in the fossil record there, including dire wolves, mammoths and saber-toothed cats.

The particular footprints from this new discovery belong to teenagers and children, which is a common finding in the archaeological world. Though we can’t know for certain why the footprints of young humans show up in the fossil record more often than adults, a leading theory is that simple gathering tasks, such as fetching water from the nearby lake, would be given to teenagers. Children would often accompany teenagers, either to assist with the task or because the teenagers were looking after them while tending to their chores. Whatever the reason, being in a large group meant more footprints, which increased the odds of fossilization and eventual discovery.

Though you may not realize it looking at it today, the White Sands area was once a lush paradise with an ancient lake called Lake Otero. It was this environment that likely brought many animals, humans included, to the area to gather food and water, leaving many tracks behind for us to find thousands of years later. Because so few tracks and debris fossilize, and even fewer are eventually discovered, fossil finds are usually found where large groups of a species existed and the conditions for fossilization are ideal. White Sands is once such place making it perhaps the most important site in the western hemisphere to study ice age ecology.

Of course those familiar with White Sands know it as a desert, and Lake Otero is nowhere in site. As the area dried and the lake disappeared, gypsum crystals were left behind which strong winds broke into the white sand we can see there today. The footprints left there now by the many visitors to the park are quickly erased in stark contrast to the 23,000-year old footprints changing history today.

Archaeologists dug trenches into the dry lakebed, finding human footprints and varying depths. They also found ancient grass seeds on layers of soil above and below the new footprints. These seeds were able to be radiocarbon dated, a process that measures atomic properties of organic material in order to determine its age. The results provided a range of 21,130 to 22,860 years ago.

The latest research was a collaborative effort between scientists from White Sands National Park, the National Park Service, U.S. Geological Survey, Bournemouth University, University of Arizona and Cornell University in connection with the park’s Native American partners.

Learn more about White Sands National Park at https://www.nps.gov/whsa/index.htm.

Artist rendering by Karen Carr